Image credit: the Fraser Institute

The fiscal approach currently taken by governments in Canada is not sustainable. Expenditures far outstrip revenues, and the balance is funded by borrowing and money-printing. In the past, Canadian politicians have been able to reign in spending and avert disaster. However, absent a complete change in the culture of the nation, this will not happen; governments are thoroughly addicted to living beyond their means, and voters have developed a deep sense of entitlement to state largesse. This will lead to political and economic crises that could spell the end of the Canadian nation-state as we know it.

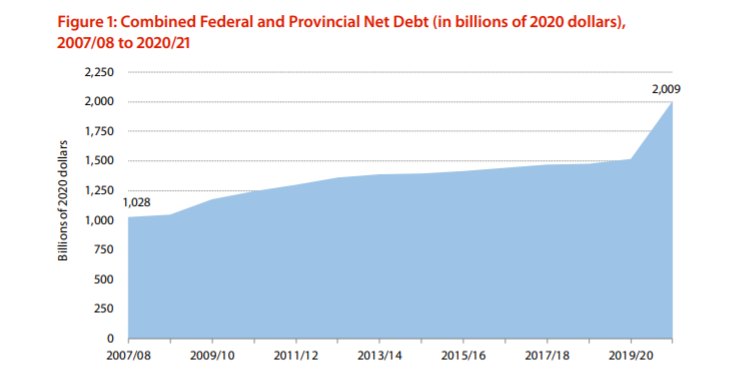

The federal debt currently sits at $1.2 trillion, and the debt to GDP ratio is 55%. Due to the lack of political will for fiscal austerity, the debt will continue to grow, and may grow rapidly, if the past two years are any indication (about ¼ of the federal debt has been accumulated since the start of 2020). This debt growth is made possible by debasing the currency, which in turn is made possible by the illusion that as long as economic growth keeps pace with spending growth a massive debt isn’t a problem.

But what is Canada’s economic growth based on? Immigration and the housing market bubble appear to be the main drivers. Canada’s population would be declining were it not for the hundreds of thousands of immigrants that arrive every year (the current numbers now exceed pre-2020 levels, and the government has set a target of 411,000 for 2022). And Canada’s GDP would be significantly lower if housing prices had not increased 64% faster than Canadians’ incomes since 2005 (with the increase especially steep in the past year). There are of course other economic drivers, such as Canada’s resource industry, manufacturing, and construction, but as regulations are piled on these industries by all levels of government, their productivity hasn’t kept pace with that of more dynamic economies, like the US.

If GDP were to drop for more than a year in a row, either due to a decrease in immigration or the real estate bubble bursting, the continued growth in the money supply would be untenable. Until now, the Bank of Canada has managed to keep interest rates artificially low without triggering massive inflation in prices (though inflation did increase sharply in 2021, and is expected to continue to rise in 2022). Under negative GDP growth, the charade that Canada will grow its way out of debt will be near impossible to maintain, resulting in a crisis of confidence in the Canadian dollar.

Just as with fiscal responsibility, I believe that the Canadian political class (and those who elected them) lacks the necessary backbone to deal with a currency crisis. How such a crisis would be resolved is anyone’s guess, but I’d like to propose one possibility in the remainder of this essay.

Canada is vast land composed of regions that differ significantly in terms of geography, economy, and demographics. The national culture is a weak one (relative to older and more homogenous countries), and regional identities, though not strong across the board (Quebec is a notable exception), seem to be growing in strength. The prospect of separatism has been part of the Canadian political landscape for decades, and there has been increased interest in greater political autonomy and even outright secession in the western provinces in recent years (40% of Albertans recently polled were in favour). Some provinces, like Alberta, might try to get out of the unfair equalization payments scheme if the opportunity ever arose, and even obvious beneficiaries of federal government handouts like Quebec and the Maritime provinces might reconsider the arrangement and go their own way if the federal government is no longer financially solvent.

So, it’s not implausible that Confederation could begin to unwind within our lifetimes. However, there are massive constitutional and political obstacles standing in the way of provinces that may wish to separate. Short of outright collapse of the federal government, perhaps the more likely scenario is that of increasing local autonomy, as higher levels of government seek to shed their fiscal obligations in line with austerity measures, which could be imposed from above by the likes of the IMF or World Bank.

I believe that in our current era, good governance happens consistently only for small political communities, where the participants have some opportunity to know each other personally, as neighbours, co-workers, and fellow members of religious and voluntary organizations. In such communities, which are not big enough to allow politicians to rise to the level of economic elites, citizens still have the opportunity to question their elected officials at town hall meetings, in the grocery store, or after Sunday service. Furthermore, such local governments do not have the power of the (money) printing press at their disposal, so that increases in spending soon result in increases in taxation, which are borne by the bulk of community members. Citizens in such communities thus expect some level of fiscal prudence, and there’s a good chance that profligate spending can be brought under control through democratic action, supported by social pressure.

The picture I’ve painted here is a traditional one, which assumes a stable membership in the community (including a high level of home/land ownership), relative economic independence (i.e. local ownership of businesses, with the lion’s share of residents’ incomes derived locally), and strong social bonds (developed from generations of cohabitation). But a small community with good governance wouldn’t necessarily need to fit the agrarian village mold. New communities could be constituted, given the right factors of cohesion, which may well be different in the 21st century and beyond.

One such factor, of course, is ideological affiliation. People who share a common political outlook, particularly if it’s at odds with the dominant society, may wish to gather together and govern themselves according to their own values. We see this approach bearing fruit in the case of the Free State Project, where libertarians have been moving to New Hampshire for several years, running for office, helping to elect pro-liberty candidates, rolling back overly restrictive laws, and perhaps most importantly, building a local culture that embraces principles of freedom and personal responsibility, bolstering autonomy from the leviathan that is the US federal government.

New Hampshire has the advantage of being a relatively small jurisdiction, both in area and population, as well as having a long pro-freedom tradition (state motto: “Live free or die”), which has made achieving a critical mass of liberty-minded citizens more feasible than it would be for, say, British Columbia (a Free Province Project did start up in 2011 with PEI as its target, but didn’t get off the ground). Nevertheless, we can imagine such a process working at the level of a municipality, township, or regional district.

How would the process work in the case of a federal (and perhaps provincial as well) government faltering under the weight of excess debt?

Political independence could of course happen by secession, either through formal channels by agreement, or with a unilateral declaration of independence accompanied by the willingness of the separatists to take up arms in defence if necessary. History has numerous examples of this route (some successful, some not), so I won’t elaborate further.

It could also happen through the formation of new settlements on the periphery of the established society. Canada has seen its share of these over the years, from Hutterite colonies to hippie communes. Such experiments in intentional communities seem to be rare these days, possibly as a result of the growth of the nanny state and its surveillance/enforcement apparatus. But that doesn’t mean a time won’t come again that’s ripe for such initiatives. A weaker federal government of the future, deep in fiscal damage control mode, might have trouble finding resources to deal with land use violations or tax non-compliance happening among a small group of people in some remote part of the country.

But I think the most likely way that political autonomy will be achieved at the local level is via an ad-hoc and incremental process of transferring responsibility for delivery of services from higher to lower levels of government. By way of example, imagine that the costs of running the socialized healthcare system in one province become insurmountable, and the chief financial officer of a regional health authority makes it publicly known that the only way to keep the system afloat is to cut loose several hospitals. One forward-thinking councilwoman in one of the affected communities proposes that the town take over operation of the hospital to keep its doors open. Patients’ rights groups, the nurses union, the hospital’s charity foundation, a local philanthropist and other interested groups then come together to work on a solution. They decide to create a not-for-profit corporation to purchase and operate the hospital. The provincial government agrees to sell the hospital for much-needed cash, and allow the hospital to be run outside the province’s (failing) healthcare insurance and delivery scheme. The provincial government gets to scratch a liability off its books; the local residents get access to healthcare services that, while not free, are of higher quality and more available than those in provincial system; and the municipal government has demonstrated that it can provide an environment where innovation and improvement in the delivery of public services can occur.

There is even greater scope for this sort of innovation governance and service delivery when we look at First Nations, particularly in BC. Because most First Nations in BC did not sign treaties with the federal government, they have not formally given up their ancestral rights to govern and care for their members as they see fit. In the past couple decades, some BC First Nations such as the Tswwassen and Nisga’a have concluded land claims negotiations with treaties that recognize some degree of self-governance. Many such claims are in process among other First Nations in the province, and may result in treaties that recognize greater levels of political autonomy. It’s not impossible to foresee a not-too-distant future where a quarter of the landmass of BC is under the jurisdiction of a couple dozen First Nations governments. We can’t predict what kind of political bent these governments would have (some could be quite laissez-faire, others highly collectivist) but the interesting thing to watch will be how open their territories are to non-indigenous people. A First Nation with a territory in close proximity to or within an urban area, that adopted a classical liberal approach to governance and economic regulation, and allowed non-members to reside and establish businesses there, might find itself a magnet for capital and a center for innovation.

Whether they be First Nations treaty lands, municipalities that love to slash red tape, or even newly formed political entities (such as off-shore seasteads), the ability for such pro-freedom jurisdictions to attract entrepreneurs and other creative people would be quite significant. This would be the case even more so if neighbouring jurisdictions suffered heavily under heavy tax burdens, poor public services, corrupt/inept/abusive governments, high levels of crime, social decay, etc. If Canadians had relatively free movement between such jurisdictions, it would make sense that over time, people and capital would migrate to places that provided the best home for them. For freedom-loving folk, that would mean places with the least government, and if those places turned out to be the most civically vibrant, least corrupt, most prosperous, and least taxed, they would provide real-world case studies on the application of libertarian ideas, encouraging citizens everywhere to favour limited government (or no government at all).

This idea of many different experiments in governance was the original model of the United States, and is a prime reason for it being the world’s greatest engine of creativity and productivity. The draconian Covid restrictions brought in by some states, but not others, have accelerated this process. Californians and New Yorkers are fleeing their increasingly authoritarian states for Republican governed ones like Texas and Florida that have done a better job of preserving the economy, civil liberties, and normalcy. Democratic Party governors haven’t yet admitted that their heavy-handed policies are driving away businesses and net tax payers, but with California and New York each losing a seat in the House of Representatives due to this population exodus, they won’t be able to obscure the reality much longer.

Governments might even be forced to implement their own diminishment because citizens can always vote with their feet, taking the tax base and their capital with them. This will be especially true if the local governments don’t have easy access to other sources of funding, like large transfers from higher levels of government, or ultra-low interest loans courtesy of central bank monetary manipulation. If escaping tyranny meant only crossing a river instead of an ocean, who wouldn’t do it? And if the positive results of good governance and state minimalism were so close at hand, only the willfully blind would deny them. I’m hopeful that the future of Canada will be a decentralized one, where citizens are able to group together according to the level of freedom and responsibility they feel is optimal, and find there suitable governance structures, and the level of taxation and government services they want, even if that means zero.

Clayton Welwood, Party President